At the end of April 2016, I received this short email from Chris Alheit:

Richard, meet Lukas. Lukas meet Richard. I know Lukas through some mutual friends. He’s just struck out on his own. I’ve tasted his barrels and think you may be interested in what he’s up to.

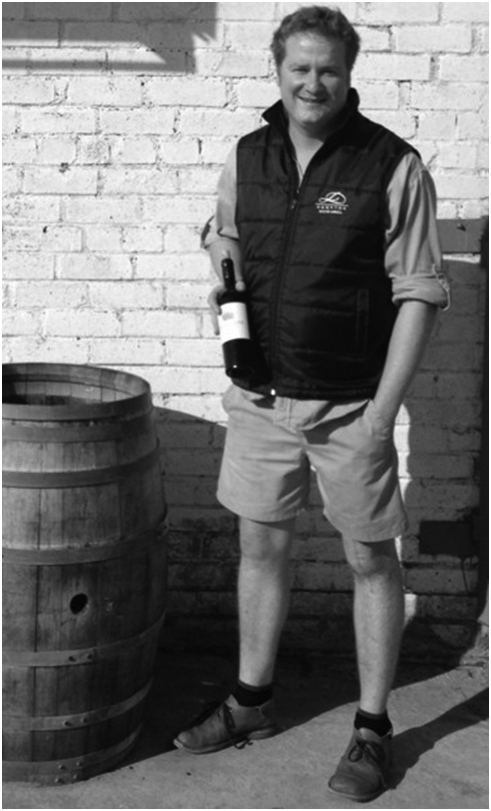

When you receive a message from such an industry luminary, I’m not one likely to ignore or dismiss such a recommendation. So, on my trip there that May, I made a point of seeking out Lukas, who is currently working out of a packing shed, previously used by Neil Ellis to store wine and equipment. Located on top of a hill in Devon Valley it forms part of a grape farm called Fransmanskraal.

Remember, this was no more than two months after he completed his first solo vintage but, as Chris Alheit had indicated, I sensed there was something quite special happening here.

– image courtesy of Tim James

Originating from Rawsonville (a town famed more for its distilling of brandy than the quality of its wine), Lukas first job was at Rijk’s in Tulbagh, after he graduated from Elsenburg college. Then, after spending two seasons on the Finger Lakes on the eastern side of the USA, he returned home to work at the relatively obscure Druk My Niet wine estate in Paarl. It was in late 2015 during a visit to France, that he made the decision to switch from being a salary-earner and into the terrifying if inevitable world of making his own wine.

So, in this large and remote shed, he produces his own wines in exchange for making a bit of (very good) Swartland Chenin for his landlord.

Lukas owns no vines, but his likable disposition has enabled him to tap into some great fruit sources, some of which are shared by the great and the good of the SA wine industry.

At what was supposed to be the start of the first vintage of Van Loggerenberg Wines, Lukas broke his knee-cap and had to undergo two major knee surgeries during harvest. But friends and family helped-out in the cellar, doing punch-downs whilst he was in hospital and arranging for a cellar hand to assist when he returned acting as an ‘extra set of legs’.” This support was part of the reason why Lukas decided to call one of his wines Kamaraderie, whilst the smashed knee-cap was undoubtedly the inspiration behind his rosé being called Break-a-Leg.

Devoted to expressing particular patches of earth, Lukas reminds visitors to his makeshift cellar that terroir is not everything and that some winemakers just have the touch and an instinct to make great wine. As a result, the relatively difficult 2016 vintage seems to have been successful for Lukas, partly due to the involvement he has within the vineyards he makes his wines from. It helps illustrate how he likes to think of himself as “a farmer rather than a winemaker”. All the wines are made without the aid of any additives, including commercial yeast.

Now for the four maiden release wines. All from the 2016 vintage, each one comes with its own individual, brightly coloured and deeply personal label. Like the wines themselves, each image tells its own story.

Kamaraderie is Chenin from old vines planted in 1960 on the Klein Drakenstein mountain, directly above the entrance to the Du Toitskloof tunnel in Paarl. For the past 50-odd years, the grapes were delivered to the co-operative in Simonsvlei. Says Lukas: “I pruned every single vine and did all the labour in the vineyards like suckering myself which allowed me to truly experience all that went into growing and making this wine.” Because of the drought, the 2016 yield was pitiable. From two hectares he harvested just 1.7 tons.

Breton is a Loire synonym for Cabernet Franc and represents three barrels from two rows of vines on the Polkadraai Hills outside of Stellenbosch; a vineyard Lukas now shares with Bruwer Raats. Like Lukas, I have a particular affinity for the Cabernet Franc from the Loire and whilst there are some excellent wines made from the grape in the Cape, they tend to aspire to being comparable to Bordeaux, rather than to those from Anjou or Touraine which are made in a more modest tradition. Lukas’s example is strictly in this more restrained style; picked earlier than is usual, it carries just 12.5% alcohol. I’m delighted that he took my inspiration for the name and also elected to bottle it in a burgundy (rather than bordelaise) bottle.

Geronimo represents four barrels from two parcels of Cinsault, half from 30 year old vines on the Bredell farm in Faure, with the balance from 45 year old material on Jacobsdal in Polkadraai. It was the ever-supportive Chris Alheit who contributed a barrels-worth of his own grapes as a birthday present to Lukas. If your experience to date is of fruity, simple modern Cinsault from the avant-garde Cape, you can be reassured that this example is altogether more serious. A lot of stems are included in the fermentation, but this is not obvious in aroma or vinous character. Unlike most, this is not really designed for drinking now and would benefit with a few years in bottle.

Break a Leg Blanc de Noir is also from Cinsault and represents just two barrels of juice sourced from the same vineyard blocks. It’s a serious, finely textured wine, one of few such South African dry rosés. It might appear expensive for a Cape rosé, but when compared to the ambitious southern Rhône versions.

| Kamaraderie | 2022 pack shot | 2022 fiche |

| 2016 pack shot | 2017 fiche | |

| Breton | 2022 pack shot | 2022 fiche |

| 2016 pack shot | 2017 fiche | |

| High Hopes | 2022 pack shot | 2022 fiche |

| Geronimo | 2022 pack shot | 2022 fiche |

| 2016 pack shot | 2017 fiche | |

| Break a Leg Blanc de Noir | 2016 pack shot | 2017 fiche |

| Graft | 2022 pack shot | 2022 fiche |

| 2017 pack shot | 2017 fiche | |

| Trust your gut | 2022 pack shot | 2022 fiche |

| 2017 fiche | ||

| Lötter Cinsaut | 2022 pack shot | 2022 fiche |